Italian Culture - Literature

From Latin to Italian

Early Italian was actually a form of late Latin – neolatino. Romance languages all evolved from Latin, the official language of the Roman Empire, and were influenced by the languages and dialects spoken by the peoples conquered by the Romans and by the different varieties of vulgar Latin actually spoken throughout the Empire, in contrast with classical, literary Latin.

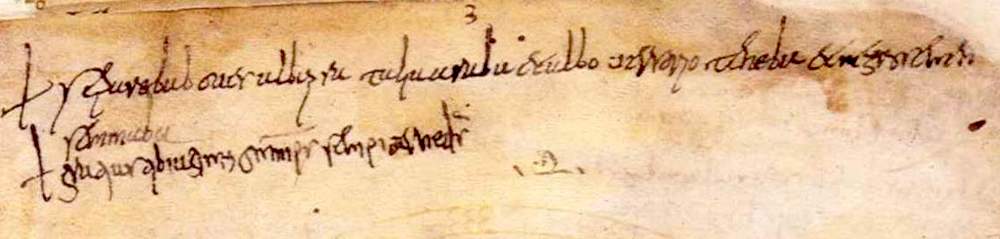

The so-called Veronese Riddle (c. 800) is one of the oldest existing documents in the Italian language, and it still sounds a lot like Latin.

Se pareba boves

alba pratalia araba

albo versorio teneba

negro semen seminaba

In front of him he led oxen

White fields he plowed

A white plow he held

A black seed he sowed.

Can you solve the riddle? The oxen are the writer’s fingers, the white fields are the paper, the white plow is the feather he uses to write and the black seed is the ink.

Early Italian was actually a multitude of regional dialects. During the 13th and 14th century, the Tuscan dialect rose to prominence as the language of literature through the works of great poets such as Dante Alighieri (1265 – 1321), Francesco Petrarca (1304 – 1374), and Giovanni Boccaccio (1313 – 1375). Dante, who chose to write his masterpiece, the Divine Comedy, in the vernacular language of Florence, also used Latin in his works, including the treatise De vulgari eloquentia, where he discusses the beauty of the vulgar or common language. To read more about him, go to this page.

For several centuries, local dialects continued to be spoken by the population of the Italian peninsula, up and beyond the political unification of Italy in 1861, when only 3% of people could speak "standard" Italian. It was only after World War II, thanks to radio and TV broadcasting and to literacy campaigns, that modern Italian was gradually adopted by the majority of the Italian people.

A Brief History of Italian Literature: Part 1 - 13th to 18th century

The six poets depicted in the painting on the left (Giorgio Vasari, Ritratto di sei poeti toscani), which includes the three masters mentioned above together with Guido Cavalcanti, Cino da Pistoia, and Guittone d’Arezzo, are considered the first great authors in the history of Italian literature, although the Sicilian School of poets, influenced by troubadours from Southern France, had already begun to use Italian in their works in the first half of the 13th century.

Alongside irreverent, comic song and poetry, the so-called dolce stil novo (sweet new style) emerged, promoting an idealised image of Love and women. In Dante’s Divine Comedy, the woman he had fallen in love with since childhood is the redeeming force that allows him to find his way through the three realms of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Love for a woman is the subject of Petrarch’s Canzoniere.

From song to poetry, to prose: Boccaccio’s Decamerone (c. 1353) is a collection of 100 tales, including love stories, jokes, and life lessons. It is considered an early Italian masterpiece and it tells a lot about everyday life in the 14th century.

On the footsteps of Petrarca and Boccaccio, the 15th century saw a revival of Latin, when erudite academics looked back to Greek and Latin classics. This was the time of humanism, centred in Florence and Naples. The rise of Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449 – 1492), called il Magnifico, as ruler of Florence and patron of artists and scholars injected new life into poetry in Italian. He is the author of the famous carnival song that begins like this:

Quant'è bella giovinezza,

Che si fugge tuttavia!

Chi vuol esser lieto, sia:

di doman non v'è certezza.

How beautiful our Youth is

That’s always flying by us!

Who’d be happy, let him be so:

Nothing’s sure about tomorrow.

English translation by A.S. Kline, 2004.

Ludovico Ariosto (1474 – 1533) is considered the most prominent author of the Italian Renaissance. He wrote L’Orlando furioso (The Frenzy of Orlando, 1516), one of the longest epic poems in European literature, which tells the fantastic story of French knight Orlando (Roland), mad with unrequited love and despair. Towards the end of the century, Torquato Tasso (1544 – 1595), another major figure of the Renaissance, composed Gerusalemme liberata (The Liberation of Jerusalem, 1581), about the epic fight for Jerusalem during the first Christan crusade.

In the 17th century prose and poetry were influenced by the Baroque taste for excess and extravagance, exemplified by Giambattista Marino's poem Adone. But this was also the time of scientist and philosopher Galileo Galilei, who used the Florentine vernacular in his works, including his Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, 1632).

The Age of Reason or Enlightenment brought a new interest in the rigorous study of economy, history, and society, and the rejection of Baroque excess and fancy. Linguistic matters were also discussed, with a lively debate about the supremacy of the Tuscan language, fiercely opposed by the so-called Lombard school. Playwright Carlo Goldoni used a completely different language and wrote most of his works in the Venetian dialect. His comedies with characters from the Venice Carnival, such as Harlequin, or other humble working-class men and women, are still very popular today.

The end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century were dominated by three main figures: classicist, dramatist, and poet Vittorio Alfieri (1749 – 1803), considered the founder of Italian tragedy; Vincenzo Monti (1754 – 1828), another classicist, especially famous for his translation of the Iliad, whose memorable opening is well-known to Italian students of all ages; and Ugo Foscolo (1778 – 1827), whose poems are full of patriotism and hope in the ideals of the French revolution, later replaced by bitter disappointment after Napoleon revealed himself as a despot and conqueror.

Part 2: 19th & 20th century

Dante Alighieri

A special place in our hearts, and on our channel, is devoted to the Father of the Italian language, Dante Alighieri. Read more about his life and works in our special guide.

Related videos on our YouTube channel

Dantedì 2020 - Canto I del PurgatorioHis First Shelter: Dante in Verona

The 10 most popular literary works in Italian

- Divina Commedia (Dante)

- I promessi sposi (Manzoni)

- Il Decamerone (Boccaccio)

- L'Orlando furioso (Ariosto)

- Canti (Leopardi)

- I Malavoglia (Verga)

- Se questo è un uomo (Levi)

- Pinocchio (Collodi)

- Il barone rampante (Calvino)

- Il nome della rosa (Eco)

Other major works

- Vita nova (Dante)

- La Gerusalemme Liberata (Tasso)

- Il gattopardo (Tomasi di Lampedusa)

- Il fu Mattia Pascal (Pirandello)

- La casa in collina (Pavese)

- Lessico famigliare (Ginzburg)

- Una donna (Aleramo)

- Gli indifferenti (Moravia)

- Canne al vento (Deledda)

- Bagheria (Maraini)

Further readings

For more in-depth information about this topic, we recommend:

Martin Maiden, A Linguistic History of Italian (2014)

Peter Hainsworth, Italian Literature: A Very Short Introduction (2012)

Francesco Petrarca, The Poetry of Petrarch (English translation by David Young, 2014)

Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (English translation by Wayne A. Rebhorn, 2013)

Alessandro Manzoni, The Betrothed (English translation by Bruce Penman, 1983)

At no additional cost to you, we will earn a commission if you make a purchase on Amazon after clicking through the links listed above. This will help support this Website.