Italian Cinema: A Brief Overview

Italy is at the same time a birthplace of Art Cinema and a major producer of genre fiction and exploitation films. With 14 Academy Awards, Italy is by far the country with the highest number of Oscar-winning international films, a record threatened only by France. This concise overview presents the history of Italian cinema from sword-and sandal films to Totò, from the great masters of Neorealism to Spaghetti Western.

Visit: The National Musem of Cinema, Turin

Part 1 - Cinema in Italy From the Beginnings to the 1950s

The Dawn of Italian Cinema

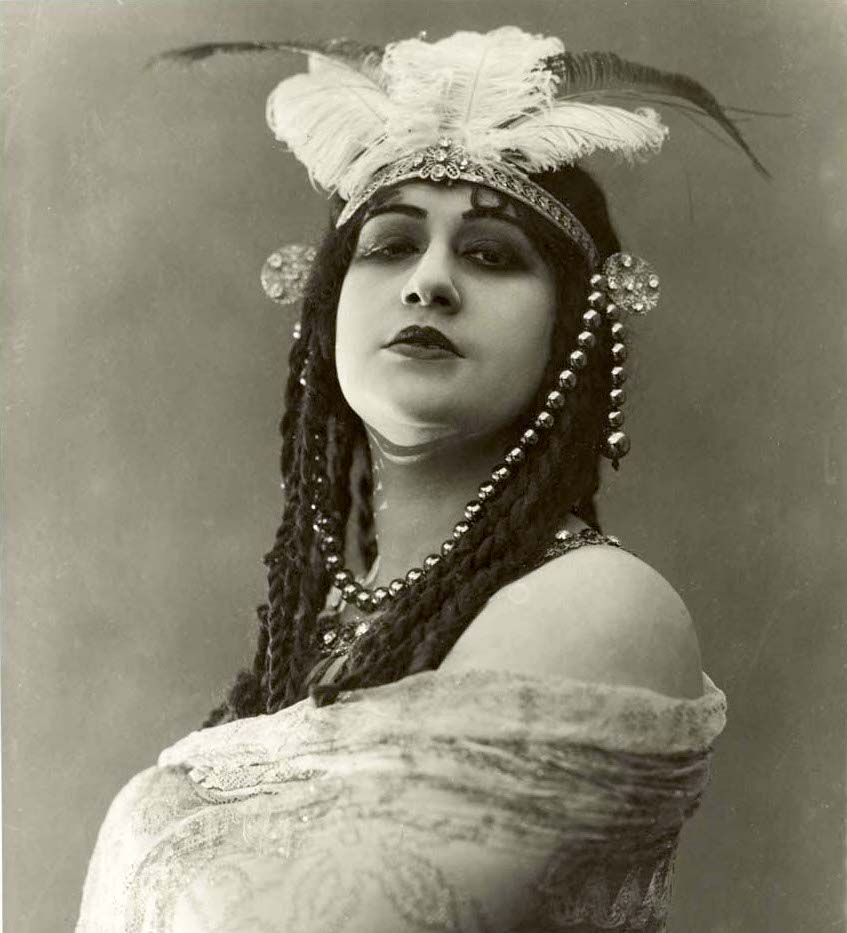

This bewitching look of yesteryear reaches us from a distant past, a time where the modern machine of cinema and mass entertainment was yet to come. Or was it?

The mysterious woman who is looking at you in the eye is an actress in one of the first Italian epic historical dramas, Cabiria, produced in 1914 in Turin, in what was then the Kingdom of Italy, by Itala Film. In 1914 Italian cinema was on a par with the great international production companies for the quality and level of its works, as demonstrated by this masterpiece of that time, produced by Giovanni Pastrone with the collaboration of Gabriele D'Annunzio (see Part 2 of our history of Italian literature). Cabiria, set in Carthage in the 3rd century, was about three hours long and was shot with hundreds of extras, elephants, impressive sets, special effects. In the history of cinema, Cabiria was the first film where the dolly (trolley), invented by Giovanni Pastrone himself, was used for filming. This Italian superspectacle stimulated public demand for features and influenced such important directors as Cecil B. DeMille, Ernst Lubitsch, and especially D.W. Griffith.

One of the main characters of Cabiria is Maciste, who totally conquered the audience. Later he became a recurring hero of many other films, turning into an icon of Italian cinema: in common parlance, the word Maciste is used to describe a man with a powerful physique and great strength.

Only 15 years earlier, the first Italian cinema hall had opened in Florence: from that moment on, Italian cinema developed rapidly and gained worldwide recognition: in 1913 Quo Vadis?, directed by Enrico Guazzoni and based on the novel with the same title by Henryk Sienkiewicz, also reached American theatres, where the ban on foreign films had finally been dropped, thus becoming a great international success.

The triumph of this film meant that Italian cinema was internationally identified with the great productions of the epic-historical genre, so much so that between 1909 and the early 1920s Italian cinema produced a dizzying number of films (in Turin alone approximately 1,400 films were made) in the wake of this international success.

Italian Cinema under Fascism

Around 1923 the Italian film system entered a deep crisis. In the 1920s only a small percentage of films were Italian productions. In the early years Mussolini, in power since 1922, was only concerned with information and propaganda, and in 1924 he established the Istituto Luce for this purpose. Fascism reacted to the crisis with a protectionist policy: it attempted to stimulate the national production by limiting the circulation of foreign films. In 1932 the Venice Film Festival was born and in 1937 Cinecittà was inaugurated. The regime used cinema as a tool for building consensus; the production grew in number, but the overall quality of the works was poor.

Since the more openly propagandistic films were not particularly successful, the regime allowed the production of light-hearted entertainment films that exalted the petty bourgeoisie and its dreams of social rise. These films often showed rich and glittering environments, so they were called "white telephone cinema", cinema dei telefoni bianchi in Italian. They were usually set in an imaginary Hungary, with attractive women from high society who used exclusively white phones to converse from home. The "white phone" was a status symbol, the icon of a luxurious world that could afford some unruliness. The first success was La canzone dell’amore (1930), and another hit was Luciano Serra pilota (1938) with the rising star Amedeo Nazzari. Mario Camerini and Alessandro Blasetti are the most representative directors of the time.

The introduction of sound encouraged the transition to cinema of comedians who performed in variety shows and theatres: Ettore Petrolini, Totò (Antonio de Curtis), Vittorio De Sica. The latter became famous by acting in Gli uomini, che mascalzoni (1932), Il signor Max (1937), and Grandi magazzini (1939), all directed by Mario Camerini.

The real break from previous cinematography and the birth of Neorealism came with Ossessione by Luchino Visconti (1943). The film follows the vicissitudes of a tramp and his mistress, accomplices in the murder of her husband. The setting, costumes and acting show a realism that was unknown at the time. After a few controversial screenings, the film was quickly taken out of circulation.

Italian Neorealism (1945-1951)

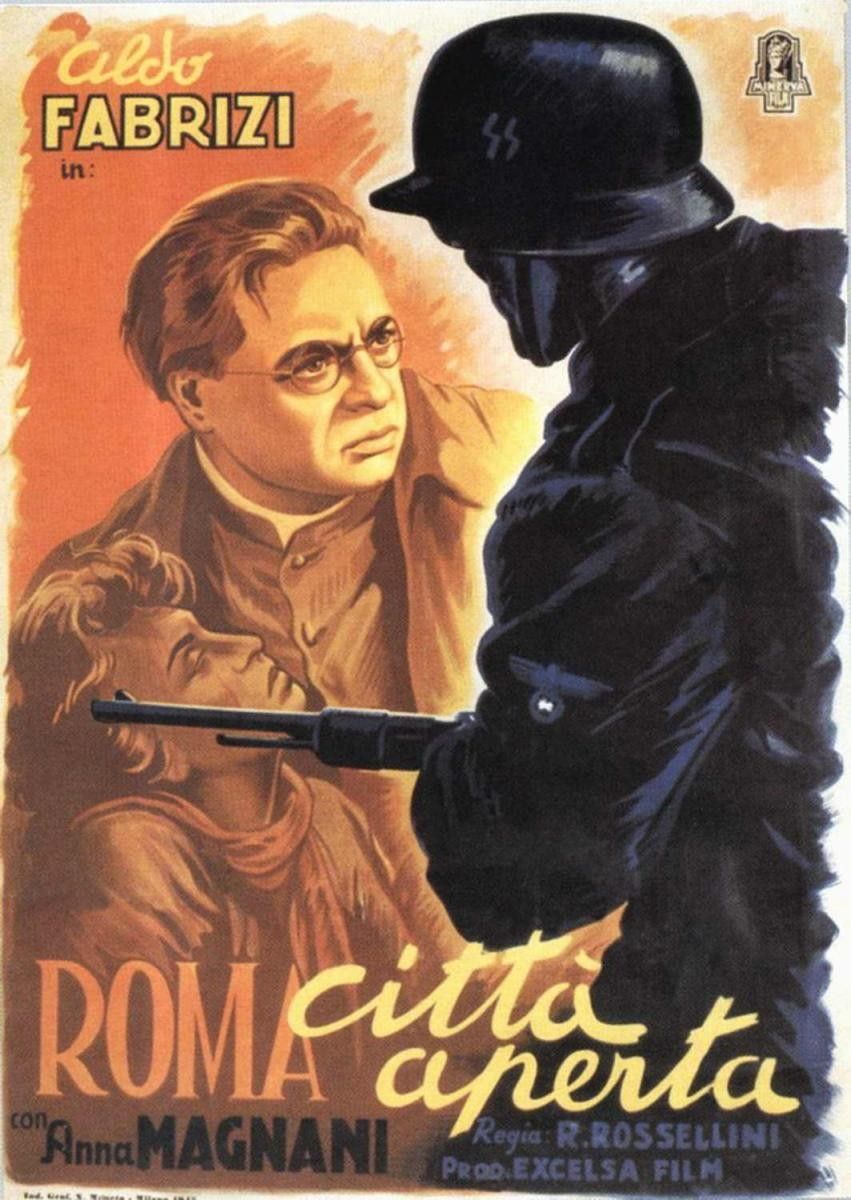

Neorealism was a cultural movement that developed in Italy between 1945 and 1951 and had its greatest expression in cinema: it had a vast and lasting impact on cinematography all over the world. Italy had managed to free itself from Fascism and the German occupation also thanks to a massive resistance movement, which helped to create a climate of hope and renewal that spread to the film world. Despite the scarce economic resources of the postwar period, a whole series of films was produced, even on a small budget, which gained international acclaim.

Neorealist films were a clear break from earlier Italian and foreign production. They were shot not only in studios, but also in the streets and in the countryside. They described the events that Italy had gone through, the partisan resistance, the social conditions of the poorer classes. For the first time the protagonists were workers, peasants, teenagers, pensioners, and retirees. Non-professional actors were also employed in some productions. These were not entertainment films, but works that critically described the difficult situation that Italy was going through, and did so in a way so close to reality that some of them can now be considered as documentaries of an era.

The most important films of this movement are Roma città aperta (R. Rossellini, 1945), Paisà (R. Rossellini, 1946), Sciuscià (V. De Sica, 1946), Germania anno zero (R. Rossellini, 1947), La terra trema (L. Visconti, from the novel "I malavoglia" by G. Verga, 1948), Ladri di biciclette (V. De Sica, 1948), Miracolo a Milano (V. De Sica, 1950), Umberto D. (V De Sica, 1951), Riso amaro (G. De Santis, 1948).

Part 2: Cinema in Italy From the 1950s to the 1970sRelated videos on our YouTube channel

Film Genres in Italian

commedia - Comedy

commedia all'italiana - Italian-style comedy

documentario - Documentary

film comico - Slapstick comedy

film d'amore - Romance

film d'animazione - Animation

film d'avventura - Adventure

film d'autore - Art film

film d'azione - Action

film dell'orrore - Horror

film di cappa e spada - Historical adventure, knights & musketeers

film di fantascienza - Science fiction

film di guerra - War & Military

film di spionaggio - Spy & Espionage

film drammatico - Drama

film giallo - Mystery & Crime

film in costume - Period & Costume

film neorealista - Italian Neorealism

film poliziesco - Detective & Crime

film storico - Historical drama

film western - Western

western all'italiana - Spaghetti western

Li conoscevo bene

I knew them well – The Movie blog for Italian language students

Teaching Italian while also talking about Italian culture is one of our passions, and this blog does a great job of bringing together language learning and the love for Italian classic films, posting cineracconti (photo-stories) in intermediate-level Italian with side-by-side English translation.

Subscribe to get weekly email notices of new posts for cinema lovers!

Also read: Understand Italian Movies Better! Common Themes in Classic Italian Movies by Judy Cohen

Further readings

For more in-depth information about this topic, we recommend:

Peter Bondanella, A History of Italian Cinema (2009)

Giorgio Bertellini, The Cinema of Italy (2005)

Peter Bondanella, The Films of Federico Fellini (Cambridge Film Classics, 1996)

Federico Fellini, Fellini on Fellini (1996)

Gian Piero Brunetta, Guida alla storia del cinema italiano: 1905-2003 (Italian, 2016)

At no additional cost to you, we will earn a commission if you make a purchase on Amazon after clicking through the links listed above. This will help support this Website.