Milano-Cortina 2026: How to Enjoy the Italian Winter Olympics

Sports events are a great opportunity to discover places you may have never seen before, or see the ones you already know from a different angle. The Giro d’Italia, one of the most important cycling races in the world, is a notable example. Now the 2026 Winter Olympics, hosted across several locations in northern Italy, will showcase not only some of our most beautiful mountain resorts, but also one of the most impressive and best preserved Roman monuments in Italy. And no, it’s not in Rome.

This year, the Olympics are back to Italy… but where exactly? Discover the venues of Milano-Cortina 2026 and learn your way around the Italian Winter Olympics.

The first polycentric Olympics

A febbraio, occhi puntati sull’Italia: this February, all eyes on Italy! The 2026 Winter Olympics will be held from 6 to 22 February in three regions of northern Italy: Lombardia, Veneto, and Trentino Alto-Adige. Fourteen different venues will host what will be i primi giochi olimpici diffusi, the first Olympic Games to adopt a polycentric approach, spreading events across multiple locations over 22,000 square kilometers.

The venues of Milano-Cortina 2026

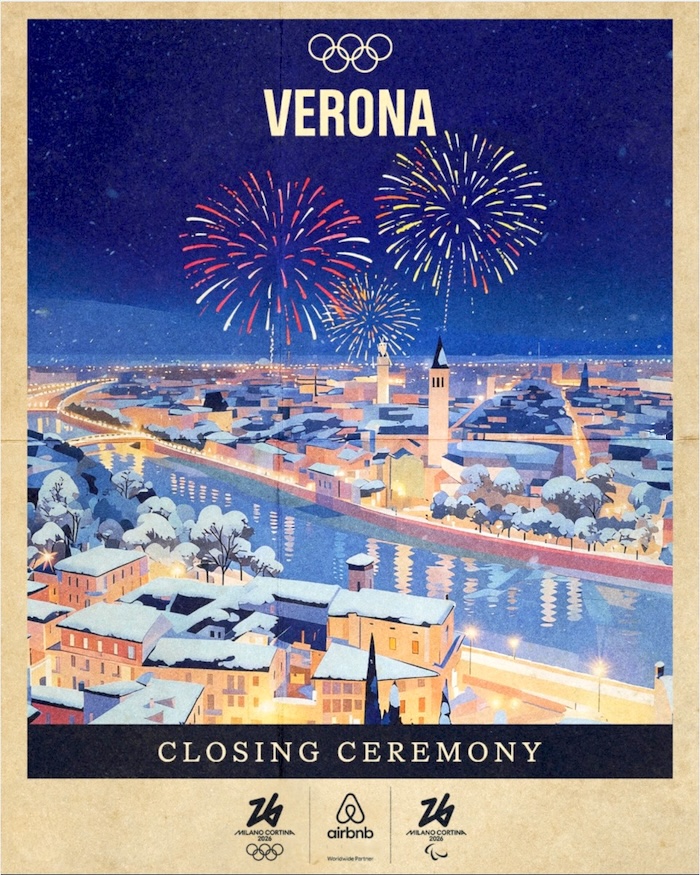

The key venues of this edition of the Winter Olympics are Milano and Cortina, of course. Milan, the capital of Lombardy, is by far the biggest city among this year’s Olympic venues, and it will host the opening ceremony and most ice sports events. It will not host the closing ceremony, though: this will take place in Verona, a much smaller city in a different region, which will also host the Paralympics opening ceremony on 6 March, 2026.

Unlike Milan, which features for the first time as an Olympic venue, the mountain town of Cortina d’Ampezzo, in Veneto, is not new to this kind of events. Cortina already hosted the Winter Olympics in 1956, the first Olympic event to be held in an Italian city.

Mountain lovers will know Cortina as an upscale tourist resort in the Dolomites, but it’s just one of the spectacular venues of the 2026 Winter Olympics: Bormio and Livigno, in Lombardy’s Valtellina, will host the main alpine skiing events; Predazzo and Tesero, in Trentino’s Val di Fiemme, will host ski jumping and cross-country skiing competitions; and Anterselva, in Alto-Adige, will host biathlon events.

Will the 2026 Olympics be a logistical nightmare?

As an article on the New York Times points out, the cross-country nature of the 2026 Winter Olympics may very well turn out to be a logistical nightmare, due to long distances, narrow roads, complex connections, and the heavy snowfall that is currently affecting Cortina and other mountain locations.

While at first snow cannons and even helicopters were being used to bring in snow to the bare slopes of the Alps and Prealps, now intensive snow storms and fog are creating even more difficulties. Travelling around northern Italy to follow the various competitions will certainly be interesting, but not just for the beautiful landscape.

You can use the official Transport MilanoCortina2026 app to calculate routes and travelling times between the venues of the 2026 Winter Olympics, but beware of overly optimistic results. Local infrastructure was improved and new tunnels were completed just before the Games, but this is still Italy, after all.

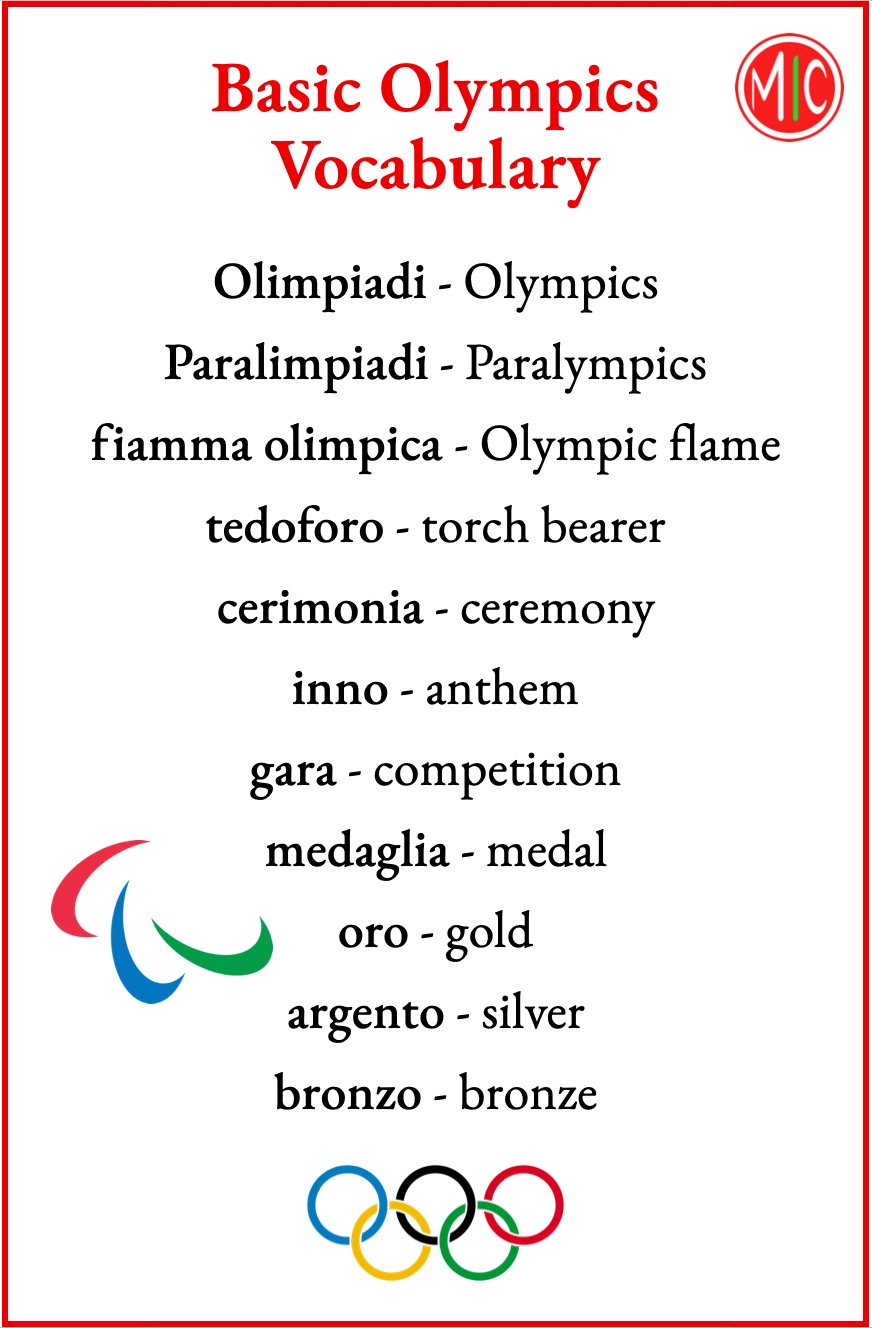

The Olympic flame crosses all 20 Italian regions

Not just northern Italy: the torch relay for the 2026 Winter Olympics – il viaggio della fiamma olimpica – touches all 20 Italian regions and 110 provinces, and some stops are truly unique. You can follow this amazing journey on the official website.

The Olympic flame left Olympia on 26 November, 2025. After travelling across Greece, the flame left Athens and arrived in Rome on 4 December. From here, it went up to Florence, travelled by sea to the islands of Sardinia and Sicily, and then moved back up through the peninsula, arriving in Turin on 11 January, 2026. Torino was the last Italian city to host the Olympic Games in 2006, fifty years after Cortina 1956.

From Turin, the Olympic flame travelled across northern Italy, reaching Verona on 18 January. On the 22nd it was on a gondola in Venice, making a historic passage down the Grand Canal. After a stop in Cortina d’Ampezzo, the torch will reach its final destination, the San Siro Stadium in Milan, just before the opening ceremony– la cerimonia di apertura – on 6 February, 2026. ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano will be one of the torch bearers on the last stop of the Olympic flame. Spaziale!

When the Olympic flame crossed the historic centre of Verona, the entire city gathered along the river Adige to witness the event. The flame was passed from one athlete or celebrity to the next, until it finally reached Sara Simeoni, the legendary high jumper who twice set a world record and won a gold medal at the Moscow Olympics in 1980. Born in the province of Verona, she is considered one of the best Italian female athletes of all time.

The closing ceremony may be the most spectacular event of the 2026 Winter Olympics

The 2026 Winter Olympics will open in one of the largest stadiums in Europe, built over a hundred years ago in 1925. This is already quite impressive, but the closing ceremony – la cerimonia di chiusura – will take place in a much older and more scenic venue: the 2,000-year old Arena, Verona’s Roman amphitheatre.

The Milano-Cortina 2026 Closing Ceremony, themed Beauty in Action, will combine art, technology, and tradition on the backdrop of the Arena, featuring opera, dance, music, and design, connecting mountains to cities and culminating in an immersive celebration of sports and Italian culture. Star dancer Roberto Bolle will appear alongside sports icons like Carolina Kostner, Deborah Compagnoni, Francesco Totti, Bebe Vio, and Jannik Sinner.

The closing ceremony will take place on 22 February from 8 pm CET, and will be broadcast worldwide. You can watch it on RAI 2 in Italy, NBC Olympics in the US, TNT Sport and Discovery+ in the UK, and many other national channels all over the world. Don’t miss it!

Visiting Italy During the Olympics?

Thinking of attending the 2026 Winter Olympics in person? Tickets for the opening ceremony range from 260 to over 2,000 euros, and accommodation at the most exclusive venues, like Cortina, have reached sky-high prices. No tickets for the closing ceremony in Verona are currently available.

Tickets for individual events and sessions are sold on the official 2026 Winter Olympics website, Milano-Cortina 2026. You will need to download the official app Tickets MilanoCortina2026 to manage your tickets, which will only be available in digital format.

Confusingly enough, there is yet another app available that provides competition schedules and the latest news about the Olympics, but also tickets and travel information on the various venues: the Olympic Games™ app.

Regardless of how you plan to experience the Olympic Games, make sure to buy tickets and hospitality packages only through official ticketing websites.

As we await the opening ceremony on 6 February, we wish all the athletes the best of luck, and may the Olympic spirit prevail over divisions and rivalries.

Buone Olimpiadi Invernali!

Diana

Related Videos on our YouTube Channel (in Italian)

- Notizie in italiano: Milano-Cortina 2026 – Learn Italian with the News

- Verona e il Veneto – Discover the rich history of Verona beyond tourist hotspots

- Bolzano e il Trentino Alto-Adige – Life in a border territory between Italy and Austria

- Bergamo e la Lombardia – Lombardy is not just Milan and Lake Como

- Torino, la prima capitale d’Italia – Where Italy was made