A Simple Guide to Italian Prepositions

What are prepositions, and why are they one of the trickiest topics of Italian grammar? English has prepositions, too, and they are not easy to master either: they are words like to, about, in, on, for. Italian prepositions are DI, A, DA, IN, CON, SU, PER, TRA, FRA. There are many more, but these are the basic ones. Again: DI, A, DA, IN, CON, SU, PER, TRA, FRA. This is the order we learn them in school, like a tongue twister. This will help you remember! Now, let’s see what they mean and how to choose one or the other.

Why Prepositions Matter

Prepositions are tiny words that contain a lot of information. They express, for example, where you are, where you are going or where you come from; the moment something happened; the position of something, and much more.

They are called prepositions because they are placed before the noun or pronoun they refer to. Remember! We never put prepositions at the end of a sentence in Italian, like you sometimes do in English. In Italian prepositions always go in front of another word:

- Di cosa stai parlando? What are you talking about?

- Con chi vai al mare? Who are you going to the seaside with?

English and Italian often use prepositions differently, so you cannot always translate them literally. For example, in English you say I live in Milan, while in Italian we don’t use IN for cities, we use A:

- Io vivo a Milano. I live in Milan.

We use IN for bigger areas, like regions or countries:

- Io vivo in Veneto, Alberto vive in Francia. I live in Veneto, Alberto lives in France.

Sometimes you need a preposition in Italian but not in English, or the other way around. It all boils down to the verb you are using. Let’s translate this sentence: I will phone/call Luca later.

Here we have two possibilities:

- Telefonerò a Luca più tardi.

- Chiamerò Luca più tardi.

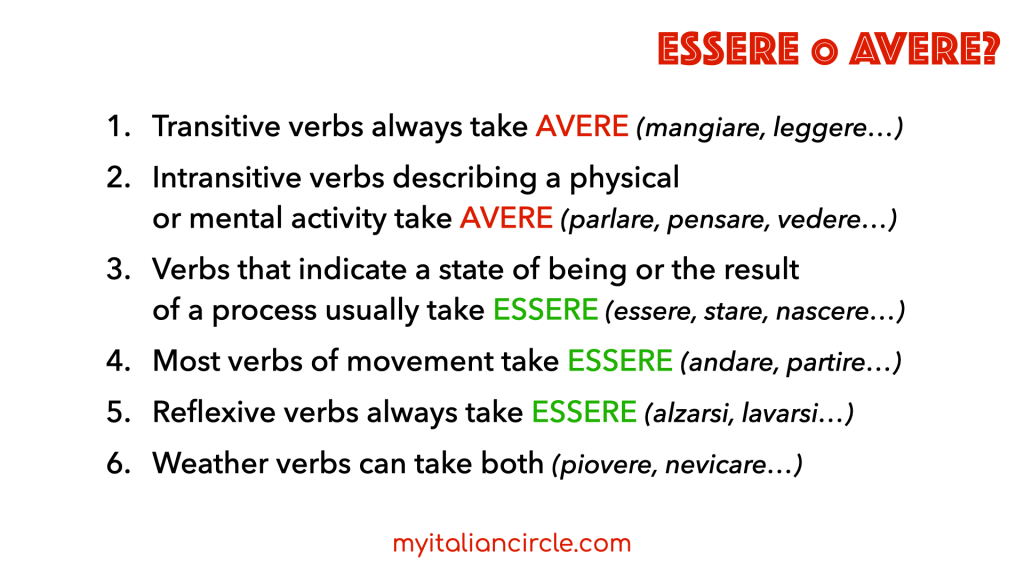

The verb chiamare is transitive and is not followed by a preposition, while the verb telefonare must be followed by the preposition A. This is why it’s a good idea to learn verbs together with the preposition(s) they are usually accompanied by.

Now let’s learn the basic meaning and usage of Italian prepositions, one by one. As you will notice, for most of them there are many different English translations. For the sake of simplicity, in this article we will not get into prepositional contractions (the combination of a preposition with a definite article), but they are very important as well. We have a video lesson on prepositional contractions and we will cover them soon here as well.

The preposition DI (of, by, on, about, from, than)

1. DI shows possession, ownership: la casa di Anita, il giardino di Ernesto, il cane di Luigi – Anita’s house, Ernesto’s garden, Luigi’s dog.

2. DI is also used to say who made, wrote, or composed something: una poesia di Ungaretti, il ponte di Renzo Piano – A poem by Ungaretti, Renzo Piano’s bridge.

3. DI introduces the topic of something:

- Oggi parliamo di grammatica. Today we talk about grammar.

- Questo è un libro di storia. This is a history book.

4. DI indicates the material something is made of: casa di carta, bottiglia di vetro – paper house, glass bottle.

5. DI shows origin, like from:

- Di dove sei? Sono di Firenze. Where are you from? I am from Florence.

All the uses mentioned above express a close relationship, similar to ownership. Here you would use several different English prepositions, but we only use DI.

6. Together with the days of the week, DI shows that something happens on a regular basis:

- Di domenica non lavoro. I don’t work on Sundays.

- Di mattina mi alzo presto. I get up early in the morning.

Here, though, you can also use the article and say: La domenica non lavoro. La mattina mi alzo presto.

7. DI is used in comparative and superlative structures:

- Alberto è più alto di Mauro. Alberto is taller than Mauro.

8. DI often introduces a verb in the infinitive in subordinate clauses:

- Penso di andare al mare. I’m thinking of going to the seaside.

- Finisco di lavorare alle cinque. I finish work at five.

The preposition A (at, to, in)

Our next preposition is A. It’s tricky because it shows movement toward a place, but also just location.

1. A is both at and to: Sono a casa / a scuola / a teatro (I am at home, at school, at the theatre), but also Vado a casa / a scuola / a teatro (I go home, to school, to the theatre).

2. A often introduces the recipient of something (the indirect object, answering the question to whom/what?):

- Ho scritto una lettera a mia sorella. I wrote a letter to my sister.

- Ho mandato un pacco a Stefano. I sent a parcel to Stefano.

3. A also shows distance:

- Abitiamo a 20 chilometri da Venezia. We live 20 kilometres from Venice.

4. A is used with some expressions of time:

- Cosa fai a Natale? What are you doing for Christmas?

- A presto! A domani! A più tardi! See you soon / tomorrow / later!

5. A can also introduce verbs in the infinitive:

- Comincia a piovere. It’s starting to rain.

- Vado a dormire. I’m going to bed.

The preposition DA (from, at, off, for, by)

1. DA translates the English from when talking about place of origin:

- Il treno viene da Milano. The train is coming from Milan.

2. We use DA with the verbs essere and stare to say that we are at someone’s place or shop, or that we are going to someone’s place or shop:

- Sono da una mia amica. I’m at a friend’s house.

- Fra poco vado da Renzo. I’m going to Renzo’s place shortly.

3. You can use DA with a verb in the present to say how long you have been doing something:

- Lavoro qui da tre mesi. I have been working here for three months.

4. DA shows the purpose of something: vestito da sposa, scarpe da ginnastica, tuta da lavoro – wedding dress, trainers, work overalls.

5. DA translates the English by in passive sentences:

- Una torta fatta da Lucia. A cake made by Lucia.

6. DA can also be followed by a verb in the infinitive when talking about things we have to do:

- C’è molto da fare! There is much to do!

- Questo è un film da vedere! This is a film you must see!

- Ho molto da imparare. I have a lot to learn.

The preposition IN (in, to, by)

1. IN shows location but also movement towards a place, just like A, but is used with different words.

- La valigia è in macchina. The suitcase is in the car.

- Sono in Italia. I am in Italy. (Remember! With cities use A: Sono a Torino.)

- Vado in ufficio / in banca / in fabbrica. I’m going to the office / to the bank / to the factory.

So, when to use IN, and when to use A? I know it sounds random, but it’s not. My advice is to memorise complete expressions, so you will just know that you should say IN ufficio and A casa, without thinking too much.

2. IN also means by when used with means of transport:

- Andiamo a Berlino in treno. We are going to Berlin by train.

- È tornata da Londra in macchina. She returned from London by car.

It’s a bit like saying that we are in the train or she was in the car.

3. IN can be used with time: in aprile, in autunno, in dieci minuti – in April, in autumn, in ten minutes.

The preposition CON (with)

1. CON corresponds to the English with:

- Stasera esco con gli amici. Tonight I’m going out with friends.

- Hanno lavorato con Arianna. They worked with Arianna.

2. CON is used to add information about something:

- Mi piacciono i dolci con il cioccolato. I like desserts with chocolate.

- Ho visto delle scarpe con i tacchi alti. I saw some high-heeled shoes.

3. CON can be used to say how something is done:

- Mangia con calma! Eat slowly!

- Taglio la carta con le forbici. I cut the paper with scissors.

- Pago con la carta di credito. I pay by credit card.

The preposition SU (on, about, out of)

1. SU basically means ON:

- L’ho comprato su internet. I bought it on the internet.

2. SU corresponds also to the English about, with reference to a topic, like DI:

- Un libro su Dante Alighieri. A book about Dante Alighieri.

3. With numbers, SU expresses a ratio: uno su tre, sette su dieci – one in three, seven out of ten

The preposition PER (for, to)

1. PER corresponds roughly to the English FOR:

- Questo regalo è per te. This gift is for you.

- Per me un caffè, grazie. A coffee for me, please.

2. Used with the passato prossimo, PER expresses the duration of an action that is no longer happening:

- Ho lavorato a Berlino per due anni. I worked in Berlin for two years (and I no longer work there).

Compare this construction with the use of DA with the present simple that we saw above:

- Lavoro a Berlino da due anni. I have been working in Berlin for two years (and I’m still working there).

3. PER shows the reason for something:

- Sono qui per lavorare. I am here to work.

- Ho cancellato il file per errore. I deleted the file by mistake.

- Ho comprato la tenda per andare in campeggio. I bought the tent to go camping.

4. With the verb partire, PER shows destination:

- Domani parto per Varsavia. I’m leaving for Warsaw tomorrow.

The prepositions TRA and FRA (between, among, in)

TRA and FRA are the same preposition, there is no difference and the choice is personal. Usually we tend to avoid repeating the same sound, so I wouldn’t say FRA fratelli, but TRA fratelli, and FRA trenta minuti instead of TRA trenta minuti.

1. TRA and FRA mean between, among:

- La biglietteria è tra il bar e il museo. The ticket office is between the bar and the museum.

- Fra tutti questi, scelgo quello blu. Of all these, I choose the blue one.

2. In reference with time, TRA and FRA also mean in:

- Sarò da te fra due ore. I’ll be with you in two hours.

That was a lot of information, and yet it’s just the tip of the iceberg. It’s a good start, though! As I mentioned above, most of the prepositions we saw today are often combined with a definite article, but their usage is the same. More about this later!

As always, practice is key. Notice which prepositions follow specific verbs when you read something in Italian. And why not, try to write simple sentences with prepositions in the comments below!

A presto,

Anna

Related video lessons:

- How to Use Italian Prepositions – Le preposizioni

- How to Use Italian Prepositional Contractions – Le preposizioni articolate

- Let’s Practise Italian Prepositions! – Esercizi con le preposizioni