If you love watching movies, you may also enjoy spotting motifs: little things – objects, concepts, design elements – that the filmmaker has added to enrich the film’s message, setting, or feeling or maybe just for fun. Many of these motifs, recurring in post-war Italian films, are examples of italianità – characteristically Italian things. Recognizing them will help you get a feel for the culture.

As I write the cineracconti (photo-stories) for my blog, I go frame by frame, making screenshots along the way. By slow, attentive viewing, I spot motifs that might otherwise fly by, perhaps to be noticed on a second – or third or fourth – encounter.

When you’re familiar with the motifs that crop up in Italian films, you’ll be alert to their coded meanings and you’ll also get it when the filmmaker uses them for comic effect.

Below, I share some motifs that have caught my eye in the post-war Italian films that I love. I hope that, once aware of these, you’ll have a deeper understanding of the films and you’ll get an idea of how to watch movies more attentively so as to get a better understanding of the filmmaker’s intent and, ultimately, to take more pleasure in what you’re seeing. Note: spoiler alert!

(For a discussion of common themes in post-war Italian films, please read my earlier article published in July 2025, right here in My Italian Circle, “Understand Italian Movies Better! Common Themes in Classic Italian Movies.”)

Oranges and Lemons

The sight, smell, or flavor of oranges is bound to make an appearance in films set in Sicily or in the South.

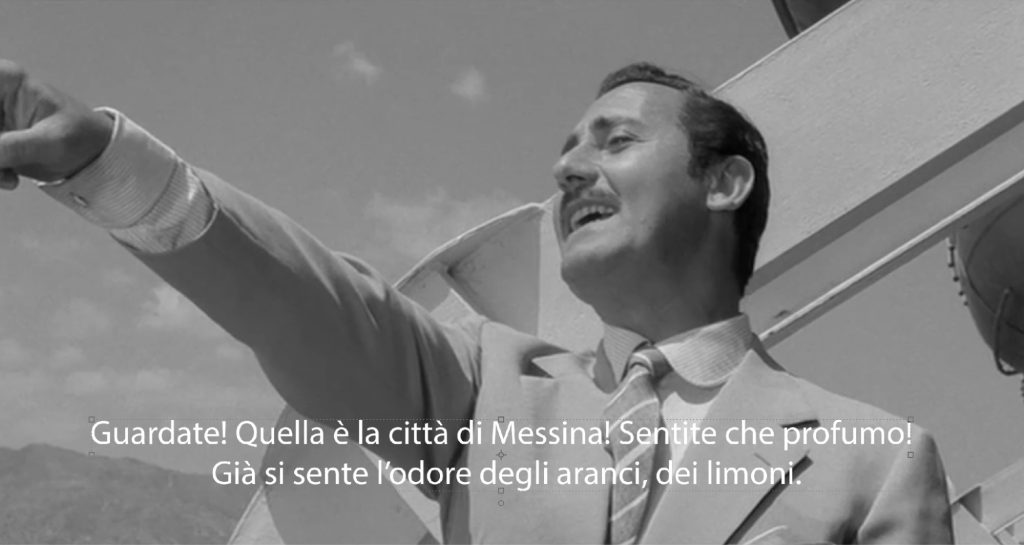

- In Mafioso, Nino (Alberto Sordi) is headed to his Sicilian hometown, along with his wife and children, who’ve never left northern Italy. As their ferry approaches Sicily, he shares his excitement.

“Look! That’s the city of Messina! Smell that fragrance! You can already smell the fragrance of oranges, of lemons.”

- In Rocco e i suoi fratelli, the Parondi brothers come north to Milan. Their first stop is a party, and they have brought oranges with them!

A party guest who also hails from the South is delighted. She exclaims, “Oranges! From our region! Thank you! What a fragrance!”

- These citrus fruits are so iconic for Sicily that they appear throughout Nuovo Cinema Paradiso as a symbol of being away from home and of coming home.

In an early scene, light floods in on a plate of lemons in front of two figures: Toto’s mother when young and when old. In the final scene, after Toto returns as an adult to visit his mother, a partially eaten orange sits between them on the table, as light filters in through lace curtains.

In a pan between little Toto and his mother across the table, a bowl of lemons links them.

Making the sign of the cross

Naturally, the church plays a big role in the lives of Italians, and so we have the motif of people making the sign of the cross.

- In I fidanzati, Giovanni (Carlo Cabrini) enters a church and automatically makes the sign of the cross, using the hand in which he holds his newspaper.

- In Ladri di biciclette, director De Sica emphasizes how compulsive this gesture is for Italians (as well as for many Catholics worldwide).

In a mad rush, church volunteers chase Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) through the chapel. But they interrupt their frantic pursuit to kneel and make the sign of the cross. Antonio’s little son Bruno (Enzo Staiola), also rushing, likewise stops, kneels, and blesses himself before hurrying on.

- Similarly, in Roma città aperta, Don Pietro (Aldo Fabrizi) and Marcello (Vito Annicchiarico), before they leave the church, kneel at the altar and then dip their hands in holy water and cross themselves.

- In La ciociara, Cesira (Sophia Loren) brings her daughter Rosetta (Eleonora Brown) to the countryside to avoid the Allied bombing in Rome. As the war nears its end, they make their way back home. Stopping in a bombed-out church, the religious Rosetta spits out her gum, genuflects, and blesses herself, though even the altar has been reduced to rubble. (Cesira doesn’t bother.)

- Commedia all’italiana director Mario Monicelli uses this gesture for a comic moment. In Risate di Gioia, madcap actress Gioia (Anna Magnani) dips her hand into the holy water and then wets Umberto’s (Totò) with her own, to save him the trouble of dipping. With this water, they each make the sign of the cross.

Communal Water Fountains – Fontanelle pubbliche

The source of water for Italy’s villages – and even some urban neighborhoods – is the communal fountain, which provides a frequent setting for film storytelling.

- Two fountains appear in the opening of Ladri di biciclette. First, we see Antonio, lounging next to a water fountain outside the employment office. His name is called for a job and he doesn’t notice, so his friend comes to find him. (“They want you. Are you deaf? Let’s go!”) Behind him, a woman kneels at the fountain, collecting water for her family. Next we see Antonio’s wife, Maria (Lianella Carell), who’s also collecting water at a communal pump.

Antonio and Maria walk home, but he’s too agitated to notice that she’s struggling with the heavy buckets.

- In Salvatore Giuliano, the military has imposed a curfew. Given just one hour to collect water and groceries, the villagers crowd around the town water pump.

- In L’onorevole Angelina, the persistent lack of water in Rome’s Pietralata neighborhood is critical to the story. Angelina (Anna Magnani) rallies the other neighborhood women to protest to the local government. Their campaign is successful, the water is fixed, and the women embark on further political action to improve their lives.

In this final image of women washing clothes together, we see the essential place of the communal water sinks in the life of the community.

- In Le quattro giornate di Napoli, filmmaker Nanni Loy placed key scenes at water fountains. In the first, a sailor – based on a real person – celebrates the end of the war with a German soldier. They ride a bike together to a fountain, where the sailor washes his face.

But, while he is washing, a German military vehicle drives by; the war is not over. When the sailor looks up, he sees the barrel of a gun; he is a prisoner of war.

In another neighborhood of now-occupied Naples, the women are warned that the Germans are rounding up men to send to labor camps. “The Germans want to pick up all the males and take them to Germany.”

Word spreads to the communal fountain, where people scatter. The camera remains focused on Maria (Lea Massari), carrying her bucket: we first meet this important character at the fountain.

Another character spotted at a water fountain is Gennaro (Domenico Formato), based on the 11-year-old resistance hero Gennaro Capuozzo. He’s come to fill his bucket.

When Gennaro sees the German jeeps coming, he runs away, beginning an adventure that will end in tragedy.

- In Il cammino della speranza, when the criminal Vanni (Franco Navarra) spots a Carabiniere, he hides his face in a nearby water fountain. The officer keeps on walking.

Living in Caves

During World War II – and in the years before and after – the poorest of the poor in Italy lived in caves. This motif has produced some powerful scenes.

- In Gli anni ruggenti, Omero (Nino Manfredi), a visitor to a town in Puglia, is mistaken for a Fascist inspector and so is wined and dined by the local officials. In this scene, he’s besieged with requests by the impoverished residents. One old woman has this message for Mussolini: “Tell him I’m in a cave with six children and a donkey.”

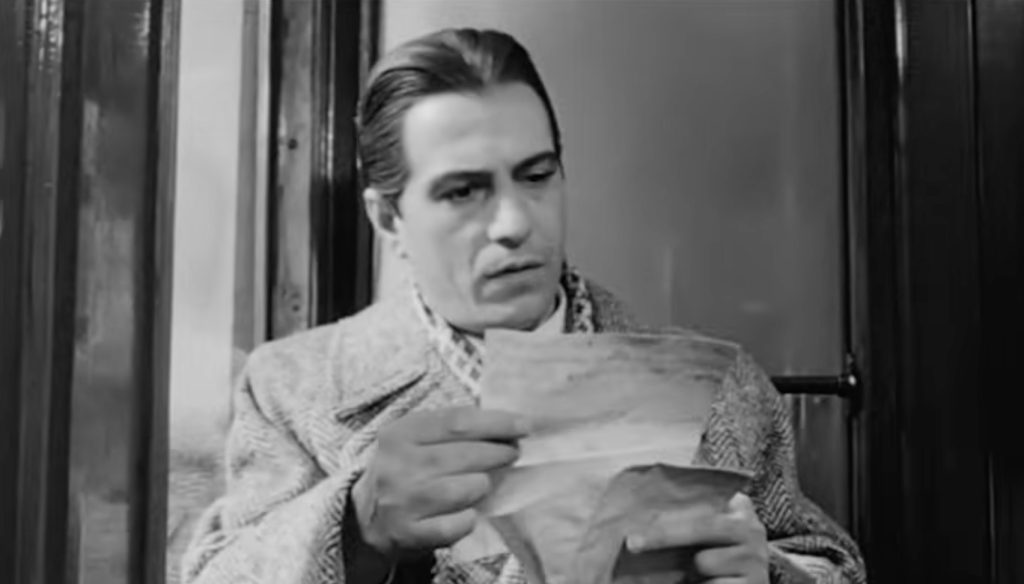

On the train, heading home, Omero reads a letter that a villager has slipped him: a simple plea to Mussolini from a cave dweller for a window. It’s clear to the viewer that no one – and certainly not il Duce – is going to do anything to help these people.

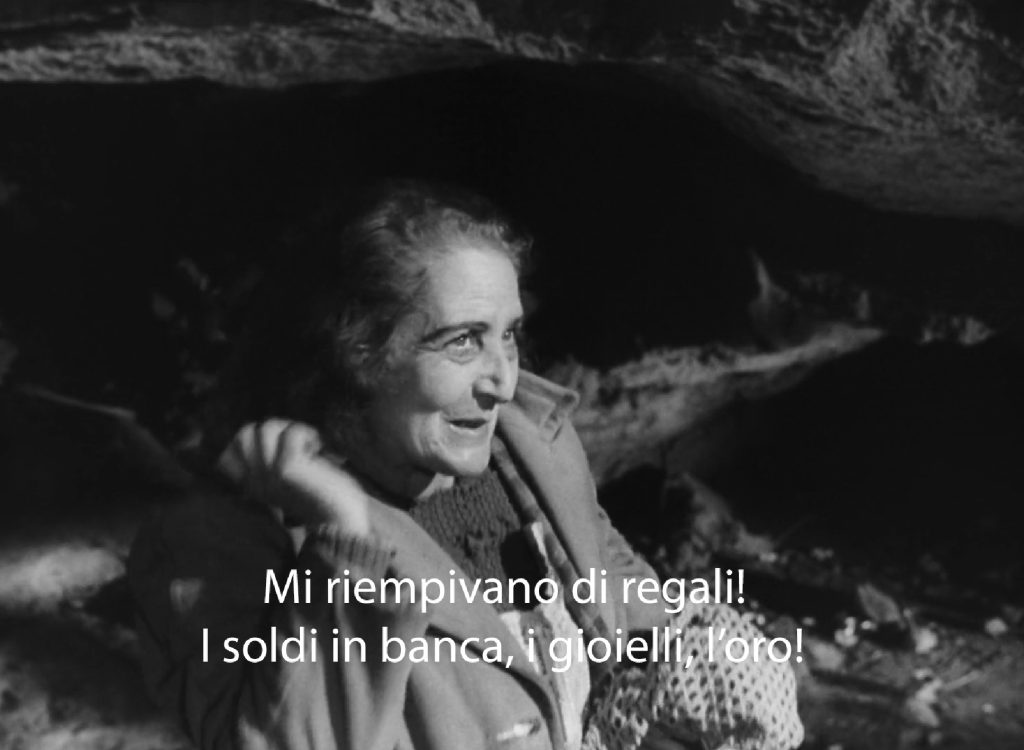

- In Le notti di Cabiria, the streetwalker Cabiria (Giulietta Masina) accompanies a good samaritan bringing food to people living in caves. Cabiria is shocked to see an old friend: Bomba, once a prosperous streetwalker: “They’d shower me with gifts, money in the bank, jewelry!”

Cabiria, seeing what her own future may be, begins a desperate effort to turn her life around.

- In the second episode of Paisà, American soldier Joe (Dots Johnson) catches a street urchin who’s stolen his boots. He forces the boy to take him home so that he can get the boots back. What he learns is that the boy, whose parents are dead, is living in a vast cave thronged with families. Horrified, Joe leaves without taking the boots.

Clotheslines – I panni stesi

- In Il bidone, about a group of scam artists, the ragged clothes hanging from clotheslines let us know that the swindlers have targeted the very poor.

- In La strada, a young woman hanging fresh laundry on a line catches the attention of the heartless Zampanò (Anthony Quinn). He hears her singing a song that he knows.

It’s a song that his companion Gelsomina used to play on her trumpet.

The woman tells him that Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina), whom he had mistreated and finally abandoned, has died. For the first time in the film, Zampanò shows emotion.

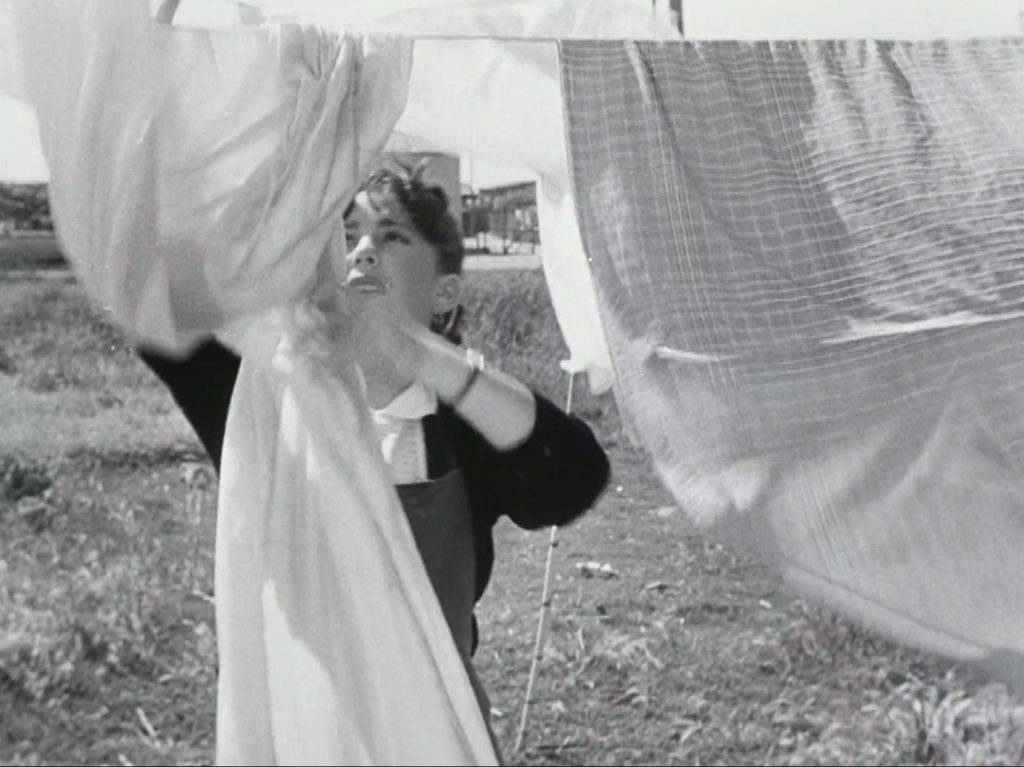

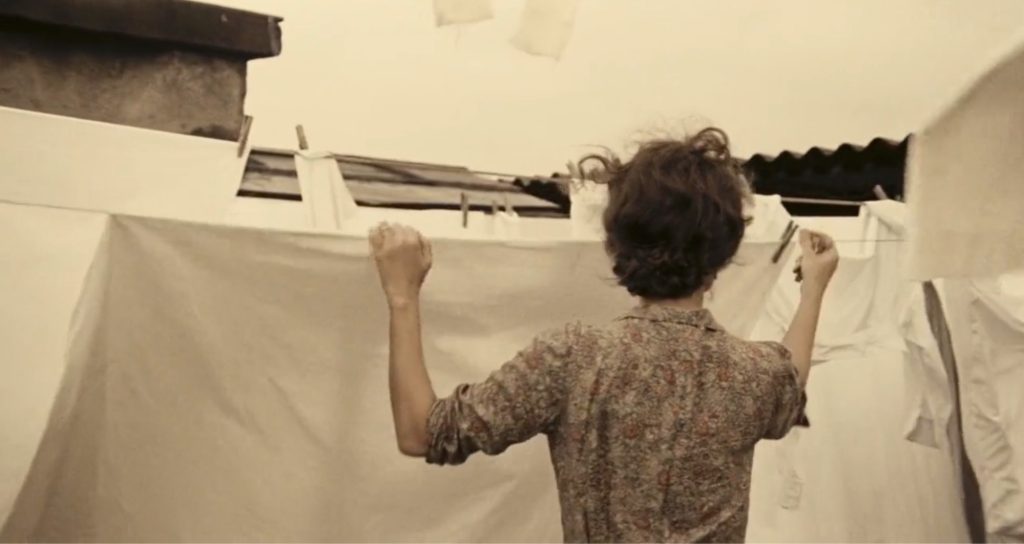

- A beautiful use of the clothes-on-the-line motif appears in Una giornata particolare, a wartime story made much later. Antonietta (Sophia Loren) is a beleaguered housewife, with six spoiled children and a brutish Fascist husband. Her neighbor Gabriele (Marcello Mastroianni) is a homosexual radio announcer, about to be sent off to internal exile. They meet by accident.

Antonietta, accompanied by Gabriele, brings her basket up to the roof to take the sheets and clothes off the line. As we witness the pair’s interactions, we hear Fascist announcements from a rally with Hitler and Mussolini in the background. The lovely white sheets loft in the breeze as the neighbors enjoy a brief moment of abandon in troubled times.

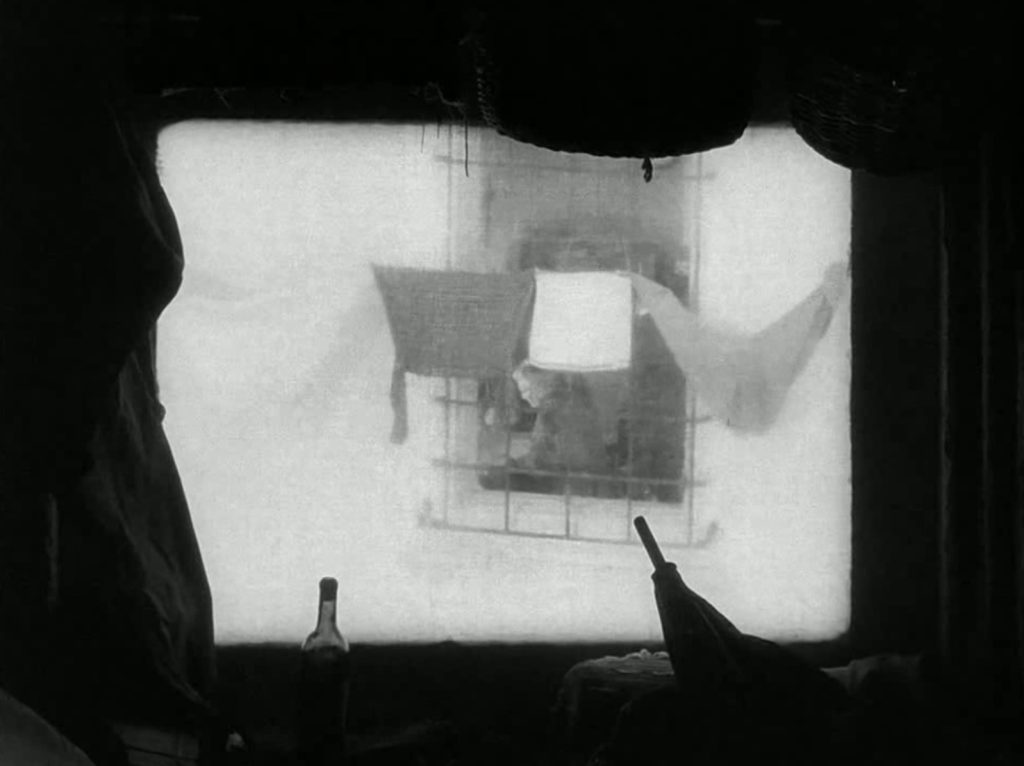

- Once a motif is established, it’s ripe for comedy. Director Mario Monicelli plays with the clothesline motif in his commedia all’italiana I soliti ignoti, about a group of bumblers planning a bank heist. First, we see a photographer’s studio where photos and underwear are hung side by side to dry on a line. Later, as the robbers plan their heist, the film they have shot of the point of entry is useless because it’s covered by washing on a line.

Finally, the thieves consult Dante (Totò), an expert, who gives them a lesson on safecracking up on the roof, surrounded by hanging laundry.

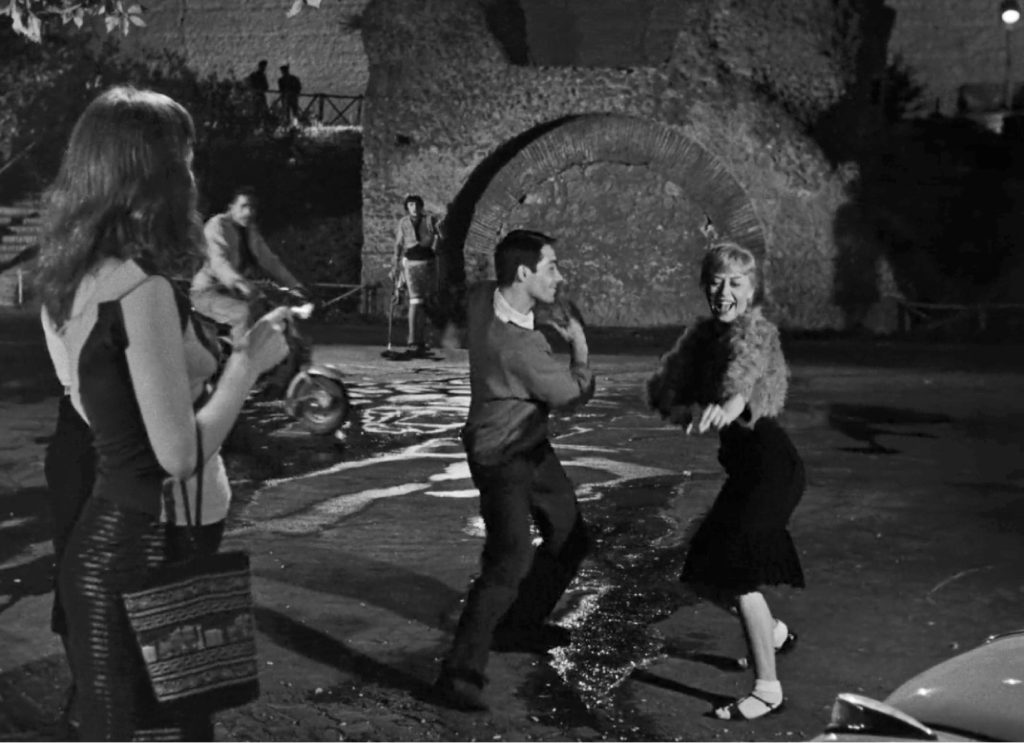

Outdoor Dancing

Reflecting a culture of sidewalk cafes and piazza life, Italian films often feature a scene of people dancing outdoors. As with the other motifs, the filmmaker may use this one as a device to say something about the characters or the situation or perhaps just as a moment of light relief for the viewer.

- In I vitelloni, Fausto (Franco Fabrizi) sets up his record player for a mambo.

But the event doesn’t go as quite as intended: Fausto and Alberto (Alberto Sordi) end up as the only ones dancing.

- In an iconic scene from Le notti di Cabiria, streetwalker Cabiria dances a carefree mambo with one of the pimps, to music from a record player. In the third image, note that Cabiria’s friend walks away for a moment to meet a potential client who’s pulled up in a car.

This scene of the ordinary – and communal – life of the streetwalkers is one of the few carefree moments of the film.

- In the neorealist melodrama Riso amaro, director De Santis, in a tribute to American pop culture, shoots his star, Silvana Mangano, dancing to boogie-woogie music on her portable record player.

This scene also stirs up a little sensuality, not much seen in neorealist films.

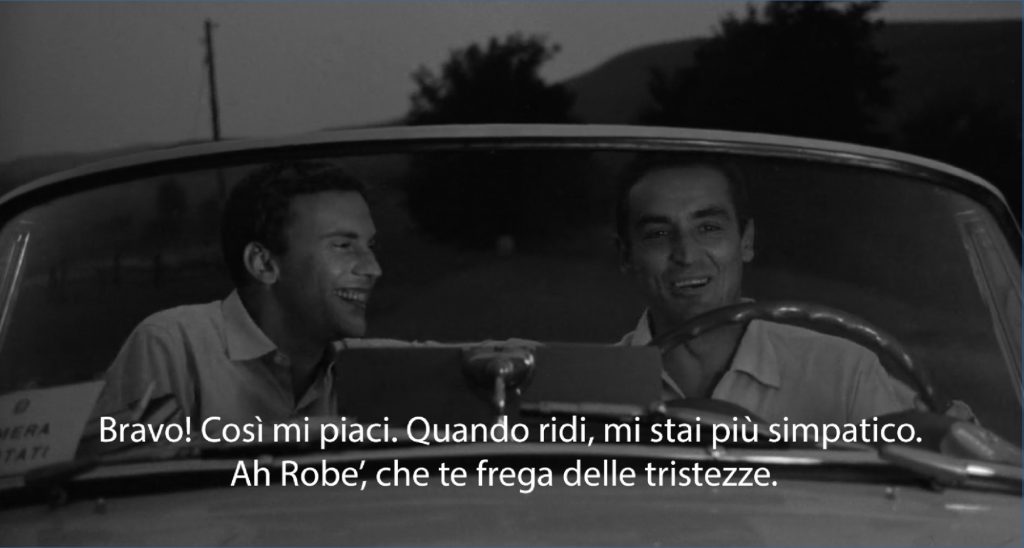

- In Il sorpasso, carefree Bruno (Vittorio Gassman) and serious Roberto (Jean-Louis Trintignant), on a road trip, drive by a meadow where country folk are dancing. They make fun of some of the characters.

This sets up the tenderest line in the film. Delighted that Roberto is finally letting go, Bruno tells him: “Well done! I like you like that. When you laugh, I like you more. Oh, Robe’, to hell with sadness.”

Train Farewells

It seems people are always leaving in Italian films. In post-war films, that is usually – though not always – by train.

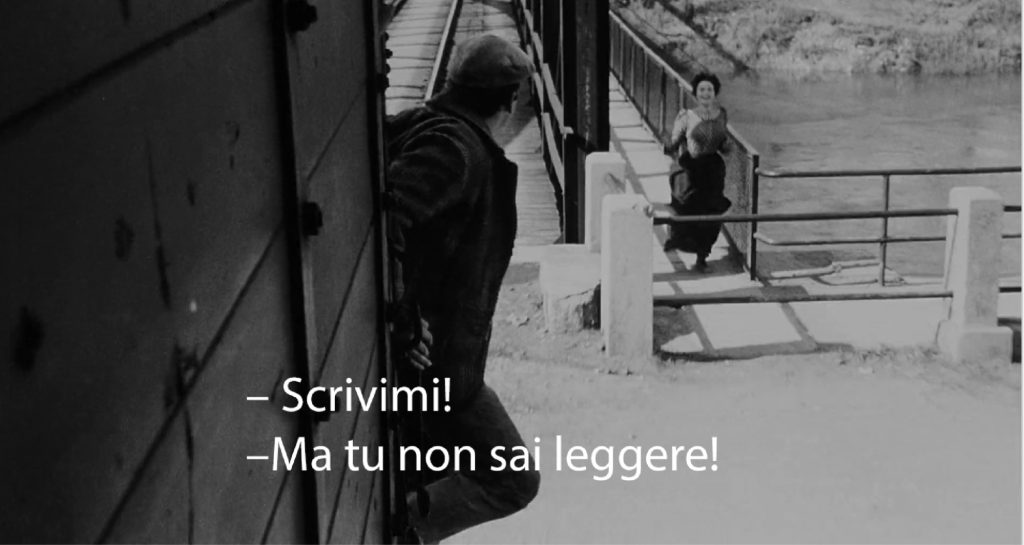

- Near the end of I compagni, Raoul (Renato Salvatori) leaves town before he can be arrested for attacking a police officer during a textile strike.

As the train roars away, Adelle (Gabriella Giorgelli) seems finally to declare her love for him: “Write to me!” He replies: “But you don’t know how to read!”

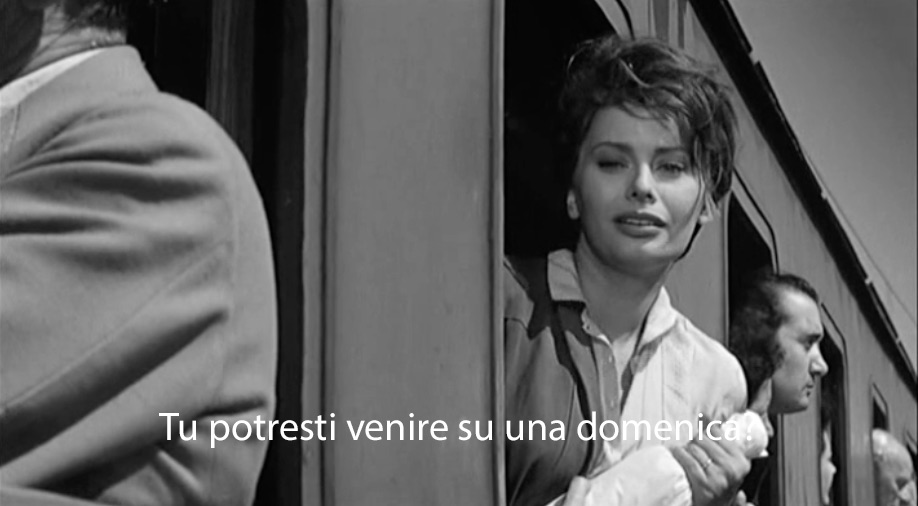

- In the World War II film La ciociara, Cesira has decided to leave Rome for the countryside to protect her daughter from the Allied bombing. She asks Giovanni (Raf Vallone), a married family friend, to take care of her shop while she’s gone. He agrees, but makes it clear that, in return, she must have sex with him.

She’s offended at the time, but when he comes to see her off, she asks, “Maybe you could come up some Sunday?”

- In I vitelloni, when Moraldo (Franco Interlenghi) finally decides to leave home, railroad worker Guido (Guido Martufi) sees him as he boards the train, and asks where he’s going, what’s he going to do, doesn’t he like their home town?

Moraldo doesn’t have any answers for Guido – or for himself.

- In order to survive, the sulfur miners of Il cammino della speranza decide to emigrate to France. They embark on a series of journeys by train, bus, and truck, which sets up a succession of goodbyes throughout the film.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this glimpse into some of the motifs that we encounter in post-war Italian films – and that these images and descriptions will inspire you to watch the films, attentive to the italianità that enriches their stories.

We’ve written cineracconti (photo-stories) about most of the films represented above, which include dialogue, scene description, and cultural notes side by side in Italian and English. We hope you’ll subscribe to the blog and enjoy reading these wonderful film stories.

Judy Cohen

judycohen.iknewthemwell@gmail.com

with

Editor: Alberto Maio

Italian teacher reviewer: Michela Badii

Proofreader: Lucrezia Grussani

Love old italian film, this will be fun!

Oh, Diane, I really appreciate your enthusiasm for reading my article! I hope you enjoy it and I hope it enhances your experience of the films you love.

Judy