Ti sei lavato i denti? Italian Reflexive Verbs

Italian reflexive verbs, a simple subject that can sometimes confuse even advanced learners!

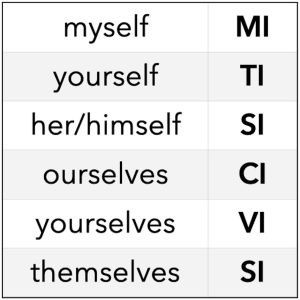

Simply put, a reflexive verb is a verb conjugated with reflexive pronouns. We call them reflexive because, in most cases, the action performed by the subject reflects on the subject: I’m enjoying myself, mi diverto.

In Italian these verbs are quite common, and you are likely to encounter them early on because many verbs that describe our daily routine are reflexive: alzarsi, lavarsi, pettinarsi, and so on.

Compare English and Italian

Italian has a higher number of reflexive verbs compared to English. However, there is positive news: English verbs that are reflexive in English are likely to be reflexive in Italian. For example:

To enjoy oneself/To have fun – Divertirsi

I am enjoying myself —> (io) mi diverto

You are enjoying yourself —>(tu) ti diverti

She/he is enjoying herself —> (lei/lui) si diverte

We are enjoying ourselves —> (noi) ci divertiamo

You are enjoying yourselves —> (voi) vi divertite

They are enjoying themselves —> (loro) si divertono

Mi lavo le mani, lavo le mie mani o mi lavo le mie mani?

Often in Italian there is a reflexive verb where in English there is a verb followed by a possessive pronoun. For example: I brush my teeth, she combs her hair: io mi lavo i denti, lei si pettina i capelli. In Italian we don’t need the possessive adjective, it’s redundant, so do not say: mi lavo le mie mani or lavo le mie mani, but simply: mi lavo le mani.

A common mistake

The infinitive form of reflexive verbs ends with the pronoun -si, so the endings of the three conjugations are not -are, -ere, -ire, but -arsi, -ersi, -irsi. A common mistake is to keep the ending -si of the infinitive when conjugating the verb. Don’t say *mi divertirsi, but mi diverto. Conjugate the verb normally, and put the reflexive pronoun before the verb.

The past tense of reflexive verbs

We can conjugate reflexive verbs in all tenses; let’s look at the passato prossimo of lavarsi. Basic rules:

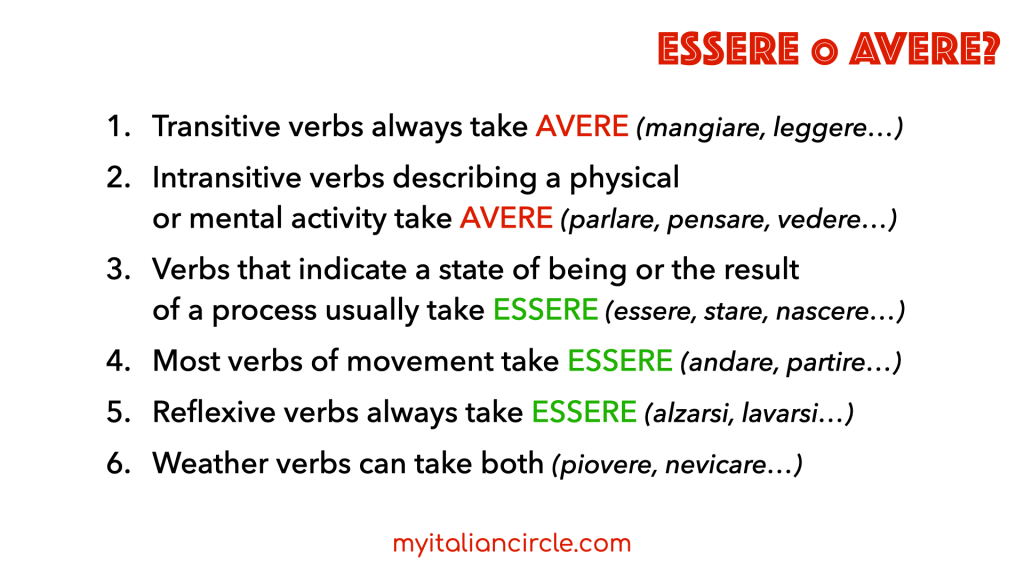

- Reflexive verbs take the auxiliary essere and not avere: sono lavato.

- Add the reflexive pronoun in front of the verb: mi sono lavato.

- Remember! When the passato prossimo is formed with essere, the past participle agrees with the subject: Elena si è lavata i denti; Leonardo e Marco si sono lavati le mani.

L’importanza di lavarsi i denti

Lavarsi i denti è importante, il mio dentista lo dice sempre! Io mi lavo i denti tutte le sere, mentre Paolo non si lava i denti prima di andare a letto, ma solo la mattina. Questa non è una buona idea! Nella mia famiglia ci laviamo i denti con molta attenzione e usiamo lo spazzolino elettrico. I miei vicini di casa non si lavano i denti molto bene, infatti hanno i denti gialli!

Brushing your teeth is important, my dentist always says so! I brush my teeth every night, while Paolo does not brush his teeth before going to bed, but only in the morning. This is not a good idea! In my family, we brush our teeth very carefully, and we use an electric toothbrush. My neighbours don’t brush their teeth very well, in fact they have yellow teeth!

In this little story the verb lavarsi is conjugated with different pronouns, could you identify them all? Write your answer in a comment below!

Alla prossima,

Anna

Related content:

- I verbi riflessivi in italiano – VIDEO